I've read recently, with much interest, a post by Martin McKeay about how he would redesign the PCI framework, as well as an in-depth summary from InfoLawGroup about the most recent entry into the draft legislation pool on security and breach notification. The more I think about this notion of creating standards and laws that spell out certain requirements, the more I think we've gotten it completely backwards. It actually makes me nervous when a regulation goes into such extensive detail, a la PCI DSS, that it tells organizations exactly what they need to do, as if one could possibly say universally what is most appropriate for every organization in their context with their own unique risk profile.

As further evidence that I think we've approach things from the wrong perspective, consider Seth Godin's recent post, "Resilience and the incredible power of slow change," in which he says:

"Cultural shifts create long terms evolutionary changes. Cultural shifts, changes in habits, technologies that slowly obsolete a product or a system are the ones that change our lives. Watch for shifts in systems and processes and expectations. That's what makes change, not big events."He's absolutely hit the nail on the head here. What we need is a culture shift, not some lightning bolt from heaven that suddenly forces a massive corrective action. We're all living with institutional inertia that greatly limits our ability to chart instantaneous course corrections. Instead of mandating long lists of penny-ante requirements, we instead need requirements that will start initiating cultural shifts. In this regard, if PCI DSS 2.0 actually contained a meaningful rewrite, then I would think the new 3-year release cycle would be ok.

In keeping with Martin's post, all of my commentary then begs the question "How would you rewrite PCI DSS to better initiate a cultural shift?" Glibly, I don't know that PCI DSS is really worth saving since it lacks legal teeth. Realistically, it seems that the card brands will continue down this path, for better or for worse, in an effort to help control (if not reduce) the fraud costs that they bear. That being said, following are some key notions that I think would be useful to see codified, either in PCI DSS or, preferably, in federal law.

Legal Defensibility

One of the first key steps is in creating the right market conditions that would encourage a cultural shift. In that regard, it seems that the logical first step would be pushing through a new legal framework that clearly and concisely creates a liability burden for all organizations as it pertains to protecting data, protecting corporate assets, and just generally implementing adequate security measures. I wrote about codifying legal defensibility in my post "Legal Defensibility Doctrine" this past March, saying:

"Part of the elegance in legal defensibility is that it is flexible in a way few other regulations currently are. And, unlike regulations like Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) or Gram-Leach-Bliley (GLBA), though legal defensibility would not specify exact technical countermeasures, it does create the basis for legal arguments that go to the heart of competence and negligence in the managing of the business. If there is one thing American business culture could use right now, then it is a legal framework that sets the machinery in motion to start building case law around what can be reasonably expected of businesses in terms of protecting themselves and building long-term value."Some will undoubtedly point to SOX and GLBA and remark that if you don't spell out detailed requirements, then nothing will get done. I think such a criticism is valid in the short-term, but goes away when the lawsuits start rolling out. Once the legal framework is in place granting standing to stakeholders, customers, stockholders, business partners, etc., independent of a demonstrated loss (or at least lowering the bar for gaining standing), then this problem ends up working itself out. The key notion to keep in mind here, though, is that we're not looking for an instantaneous change, but rather expect - realistically - to see changes slowly build momentum over the course of several years. You'll first get initial cases that have no real precedent, but then as the judiciary and plaintiffs begin to improve their awareness and savvy, suddenly there will be a surge that helps build significant precedence and case law around the topic.

In the end, then, this cultural shift will hinge on what is or is not "reasonably foreseeable." The arguments around this topic could be epic, but it also shifts the nature of the conversation. If your organization has already proactively built a legal defense that documents your security decisions using sound decision analysis methods, then the burden will shift to the plaintiff to demonstrate that your organization was negligent, which I believe will ultimately come back to this idea of "reasonably foreseeable." Ever better, the courts already have experience with this topic when it comes to data retention, legal holds, and the like, which will I think lead to a better world for all (or so I can dream).

Formal Risk Analysis

At it's core, legal defensibility is really just a risk management strategy, which means that you would necessarily need to perform formal risk analysis. Nonetheless, it seems to make sense to somehow mandate use of formal risk analysis methods as part of an overall decision management approach. How one would go about doing this in a regulation is perhaps a bit squishy, but I think that if you combine it with a mandate for legal defensibility, then it follows naturally that if your decisions are not made on reasonably sound risk analyses, then your position will become less defensible. Such a mandate in this area could also help spur investment and research into this area to help move things forward.

Mandatory Breach Reporting

While it is an urban legend that there isn't adequate data to perform a reasonable quantitative risk analysis, it is still increasingly important that we improve our data around security and breaches. Whether public or private, all breaches should be mandatorily reported to a national data breach clearinghouse (like DatalossDB.org) where the data can be reasonably anonymized (not that it necessarily needs to be) and classified according to a consistent taxonomy (sector, size, nature of the breach, etc., such as VerIS Framework might provide).

Mandatory breach reporting is needed for two main purposes. First, it leads to an improved sense of transparency that is necessary to help rebuild trust relationships. If organizations are working through breaches in secret, then how can we as consumers, stakeholders, stockholders, business partners, or even regulators work to document conformance with the above principles? Second, breach reporting will help us better understand the threat landscape. We know that a handful of large breaches in the past couple years leveraged off a fairly antiquated SQL injection attack. If we had more data, then we could start putting some bricks in place in the foundation of what is "reasonably foreseeable," which in turn would help drive legally defensible strategies.

Common-Sense Policies

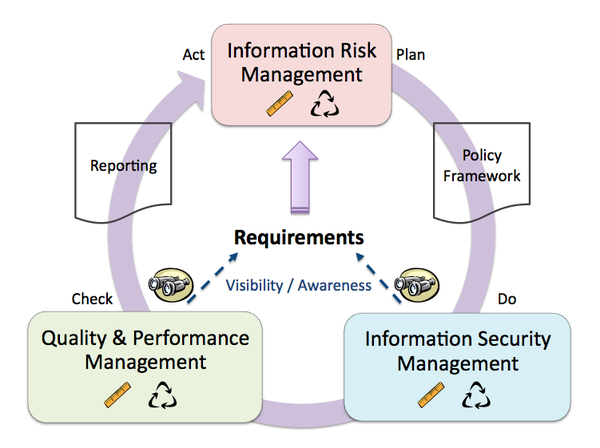

One thing Martin says that I disagree with is that "Everything flows from policy." I don't actually believe this to be true, and in fact would argue that policies are at best the 3rd step in the chain after thoroughly defining business requirements and performing a comprehensive risk analysis. Consider v2 of the TEAM Model:

The business, and by extension its various requirements, must be at the core of any security program. Once you define what's important and necessary, then and only then can you then progress to determining risk tolerance. Once requirements and risk tolerance are establish, THEN you can proceed to writing security policies that are applicable to the business and useful.

Unfortunately, today we don't generally have sensible policies. They're rarely linked to either business requirements or a risk management strategy beyond meeting a compliance checklist item. Case-in-point, as I noted earlier this month, consider policy requirements for passwords (see: "Password Complexity is Lame"). They typically focus on complexity, when the simple fact is that length is now more important (ref: "Short passwords 'hopelessly inadequate', say boffins").

The point here is this: policies should be driven by the risk management strategy, which should in turn by driven by the business and business requirements. In this sense, everything flows from the business, not from policies. We need to make sure that policies are relevant, sensible, and enforceable so that they will contribute to the desired cultural shift.

Closing Thoughts

There are likely other areas that should be considered for inclusion, too, such as reforming awareness training to an approach that further enables culture shifting. The trick to regulations like these is creating the conditions that make cultural change natural and (reasonably) optimal. The idea is that you allow people to make their own decisions, but that you encourage a preferred decision by making it less painful than other possible choices. Specifically, by creating a regulatory environment where making sound, well-reasoned choices works in your favor, while making poor choices results in strong negative consequences, then we can start to have hope once again that executives will start to understand the need for a new direction. For employees, this approach ideally drives a narrowing of the human paradox gap, increasing the connection between actions and consequences.

It seems natural that some form of regulation is necessary today. Unfortunately, we live in a bog of our making, mired in checklists and faux best practices. Until we can shift culture away from this failed mindset to something much more prescient, we will only continue to see the same problems repeating over and over again. While industry regulations like PCI DSS may have moved the needle a little bit, their impact has not generally encompassed the whole of the enterprise, but rather been partitioned in such a manner as to minimize the overall effect on the business. It's time to change things up, eliminating exceptions and mandating what is sensible and useful. If we create the right environment for generating good decision-making, then there is hope that it will lead to a desirable culture shift.

Excellent post. Another area I'd like to see ingrained culturally is measuring the performance of security services i.e. metrics. As you mention, over time we'll standardize on which metrics and target values are Defensible. Audits are fine for verifying policy conformance. However metrics shine accountability on sustained performance. Metrics are a wonderful culture hack.

ps. "culture hacks" has a nice ring to it. Might make for a good blog series?